A while back, I wrote about a school district in Texas that was working to oppose public housing in its borders. The underlying assumption was that kids from projects are more costly to educate, taking up more resources from the teachers and leaving less for the other kids. I used that example to talk about why the incorporation of suburbs is problematic from a regional economic point of view – suburban folks often receive great economic and cultural benefits from living near the city, but are insulated from having to spend tax dollars supporting folks not wealthy enough to move out of the central city.

I want to talk today, though, about the ways in which white flight and the depopulation of cities in the twentieth century are in many ways similar to the current conversation surrounding school choice. Before I start, though, two disclaimers:

- I know very, very little about education policy, so I’m approaching this from a planning and social policy perspective. If you know more about education than I do and I’m not getting something quite right, let me know in the comments!

- For the sake of the argument to follow, I’m going to assume that the public schools people move away from are in fact poor schools. I don’t believe this assumption is true as a blanket statement. Much ink has been spilled showing that whiter, wealthier kids do better on standardized tests than other kids who read, write, and do math at the same level. When people compare the test scores of different schools, they might just be noticing which schools have kids better trained at taking standardized tests. Furthermore, comparing standardized tests doesn’t make sense as a way of judging how well your kid would do in a school. If you did put faith in standardized tests, you’d want to see how kids in the same situation as yours (family income, initial literacy, etc.) did in each of the schools. If kids from tougher backgrounds do worse on testing than others, and two identical schools have different populations, the average test score will be different even if similarly situated kids do identically. And, even if a “worse” school would lead to lower academic achievement, Abby Norman explains in a piece I can’t recommend highly enough why the human experience in a low-performing school can more than compensate for this academic loss.

The second assumption above is a tough one for me to swallow – in case the entire paragraph of explanation wasn’t enough to communicate that. It’s something that I might well engage with more at another time, but for now I’ll just say that if you can accept the baseline assumptions of someone with whom you disagree (“Inner city schools are bad!”) and still explain why their conclusions are problematic, you’re likely to have more luck getting them to engage.

Earlier this week, the Times had a piece (I feel like all my blog posts start with an article from the Times – I also read other sources too, I swear!) entitled Good Schools, Affordable Homes: Finding Suburban Sweet Spots. The authors begin their article with the following: “For better or worse, it’s common for city-dwelling families that reach a certain size to make the leap to the suburbs for more space and better schools.” Right off the bat, I’ve got a problem with this article. The authors preface their sentence with “[f]or better or worse” in order to demonstrate their ambivalence, but spend no time discussing whether or not it is better or worse. They leave undisturbed what is, to this planner’s eye, the single factor most undermining American public education. I posted the article on Reddit, and someone quickly commented that, in their city, a family is forced to either cough up the money for private school or move out of the city. I’ll be coming back to that.

I’ve been meaning to write a piece about white flight and the impact housing policy had on minority communities, both before and after the Supreme Court’s ruling in 1948 striking down racially restrictive covenants. But it’s a big topic that I’m still grappling with. Without going into the details, though, we know that white flight led to a huge migration of relatively affluent people out of the cities. This was due to many things, though racism did play a big part. As people of color (who were often poor) moved into their neighborhoods, those who could leave did so. Those of us who spend a lot of time thinking about these things have a pretty negative view of the depopulation of urban cores. This led to racial and financial segregation. The segregation became especially visible when suburbs enforced minimum lot sizes, effectively setting minimum house prices and locking out those who couldn’t afford them. As the tax base left, the quality of services in the cities deteriorated. As the wealthier people left, politicians spent less of their capital on these areas. The outward migration led to huge amounts of sprawl, and accounts for a large chunk of why we’re so dependent on automobiles in this country.

And yet, for many of the individual families who moved out, it was a no-brainer. Property values were falling, so they wanted to sell before they went even lower. As the neighborhood grew poorer, there may have been more crime that they wanted to escape and insulate their families from. Jobs moved where the people went, so even the holdouts eventually moved to be closer to work. To hold these individuals who moved responsible is difficult. And yet, with each family that did move, the cycle only reinforced itself. A lot of people making choices that were in their own best interest led to massive negative social externalities. The result is Donald Trump’s thunderous (and erroneous) claims about the violence and crime in our inner cities.

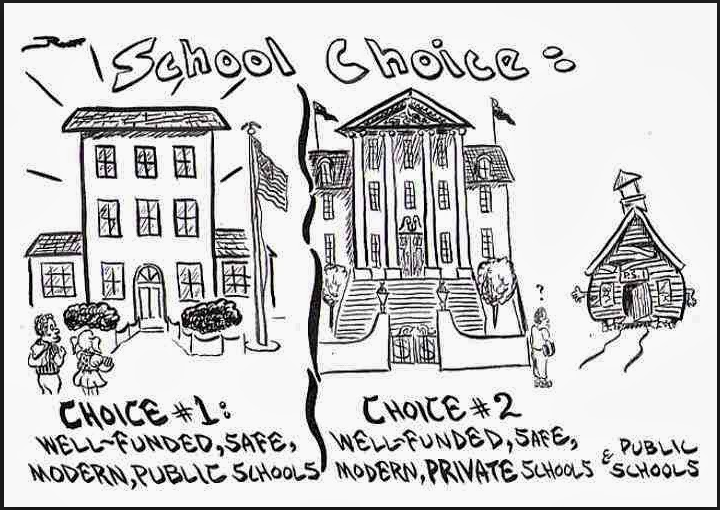

So what does this mean for school choice? Because parents who really think that they’re doing what’s best for their kids are trying to move them out of the bad schools. In fact, as the Reddit commenter I mentioned earlier and the other parents in Norman’s piece reveal, most of these parents aren’t even considering sending their kids to the local public school. The choice many of these parents want is not between the local public school and a private one they can’t afford. They want to be able to send their kid to a better school without having to pay for it and without having to move. And, assuming that they are right and that the kid will have a better academic experience at a private school, they’re only doing what’s best for their kid. But it’s the same cycle as we saw in urban depopulation – each time a family of relative means pulls their kid out of the public school, they are withdrawing their resources (financial and otherwise) from that community. What’s in their best interest is detrimental to the remaining community that may have relied on that families taxes, or those parents’ availability to fight for improved schools or ability to speak the same language (literally and figuratively) as the policy makers. If the only folks who continue to have their kids in the schools are those working multiple jobs or those unfamiliar with the ways in which policy is shaped, are they likely to ever improve? More likely, like a GOP insurance plan from which healthy people are allowed to leave, the system collapses.

We’ve made this mistake once with the mortgage interest deduction. Through the Federal Housing Authority’s liberal use of redlining, the federal government subsidized white families trying to escape poor inner city neighborhoods. Make no mistake – it wouldn’t have happened to anywhere near the same extent in a free market. And this exodus of wealth and political capital led to the absolute collapse, for many decades, of the areas left behind. Despite superficial differences, any voucher program creates the same problem. Relatively wealthy families will be able to pay the difference between the value of the voucher and the private schools. Poorer families, unable to pay that difference, will have been in actual fact extended no choice at all. As the families who are already better off, and therefore statistically more likely to be white and conversant in political discourse, leave the public schools, their potential advocacy will leave as well. And under a voucher system, we’d be giving the money to make it happen. We would be using public funds to create negative externalities.

We’re not going to outlaw private schools, and we’re not going to legislate against moving for the purpose of better schools. We can, however, take a stand on the voucher issue. To the families who want to take the money that would have been spent on their kid in a public school and use it for a private school, we can say “Tough luck.” That public education had strings attached. The free education was conditional on your participation in the community. If a parent chooses not to participate in the community, that’s their choice. They can choose to do what’s best for their kid at the expense of the community; to expect many families to do otherwise would be foolish. We shouldn’t pass judgement on folks trying to do what’s best for their kids; that’s human nature. But if they’re going to take their kids out of the public schools, if they’re going to cause negative externalities, we shouldn’t endorse that by handing over public funds to go with them.